THE 10 SEEDS OF FRUTO 2018

After several enriching debates, FRUTO 2018 generated 10 seeds to be planted and cultivated by everyone, written by environmental journalist Claudio Angelo, author of the book “Espiral da Morte” (Spiral of Death), winner of Jabuti Prize in 2017.

1

THE HUMANKIND IS IN A DIETARY CROSSROADS

In the next 40 years, it will be necessary to produce the same quantity of food we have produced during the entire last eight millennia. It will be necessary to feed 9 billion people in 2050, also counting on an expansion of the middle class in Africa and Asia, which will double the food consumption per capita. All of that in a world where 815 million people starve and 1,5 billion are over-nurtured.

2

THE CURRENT PRODUCTION SYSTEM IS KILLING THE PLANET

Farming is the largest impact human activity on the planet today. We use natural resources equivalent to one Earth and a half, what means a robbery to natural resources in broad daylight. About 70% of the habitats conversions and biodiversity loss are due to food production. In Brazil, we have already lost 20% of Amazon, 50% of Cerrado and 93% of our Atlantic Rainforest. And the pressure over the earth and sea ecosystems is constantly growing.

3

THE CHALLENGES ARE UNPRECEDENTED AND OF MULTIPLE ORDERS

Over the next decades, it will be necessary to produce more food using less resources. That is especially challenging in a world where the production and food distribution system is concentrated on the hands of few corporations and follows the global economics logical instead of the logical of feeding humankind.

4

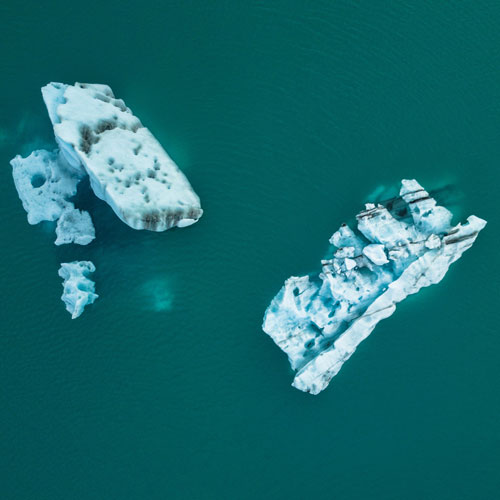

THE CLIMATE CHANGE INCREASES THE DRAMA

Global warming has been reducing cultivation areas all over the world at a speed bigger than all studies predicted. The amount of degraded grounds can double by the end of the century and among the most vulnerable areas are the ones in which the poorest farmers live, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Northeast region of Brazil.

5

SOLUTIONS ARE ALSO MULTIPLE

There isn’t one single recipe on how to overcome the challenge to feed humankind properly. Part of the answer lies in science, with the development of vertical agriculture adapted to the cities; also in genetical engineering and other agricultural technologies, in order to increase the cultures resistance to climate change and amplify the efficiency of photosynthesis. However, part of the answer also relies on techniques such as syntropic agriculture, that doesn’t use chemical incomes, and organic production.

6

THE FOOD PRODUCER IS AN ALLY, NOT THE VILLAIN

Trawler fisherman don’t kill sharks and dolphins because they want to, but because they lack the opportunity to do it differently. One quarter of farmers don’t cause half their impact because they are evil, but for lack of resources. This share of food producers must be target to efficiency and quality increasing policies. They must be included in new production models and not demonized.

7

THE TRADITIONAL POPULATIONS WILL BE INCREASINGLY MORE IMPORTANT

Indigenous, Quilombola and other kinds of farmers communities that possess traditional knowledge have a key role in XXI century feeding. As guardians of the cultivating diversity and “live pantry” that are the natural ecosystems, these people are the main barrier against genetical erosion caused by commercial agriculture, which reduces the variety of food that gets to our table as well as the resilience of the farming system itself, dominated by a handful of plants. They must have the integrity of their territories assured and their products integrated into modern commerce systems, so they may come out of the forest and reach the table.

8

THE OCEANS ARE THE NEXT FRONTIER

The projected increase on the animal protein demand is 80% by 2050. Fish can help to supply great part of that additional demand at a fraction of the environmental and financial costs. However, it will be necessary to further develop aquaculture, since wild fish can no longer supply the market, and radically change the way fishing is made: 80% of the populations are exhausted or overexploited and 40% of all sea extraction is accidental capture (bycatch).

9

IT IS NECESSARY TO STRENGTHEN THE LOCAL FEEDING SYSTEM

Culture begins to be seen as a comparative advantage, and gastronomy is an essential part of that new economy. The gastronomic and touristic revolution in Peru shows how countries that are cultural and gastronomic diverse, such as Brazil, can transform this into competitive advantage – generating revenue, soft power and, at the same time, protecting the peasants and the diversity of local food.